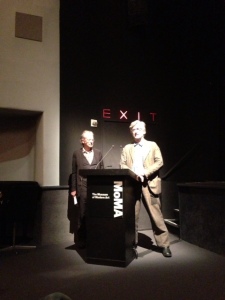

Among the world’s most prominent independent filmmakers, Wim Wenders has finally been honored with a retrospective at the Museum of Modern Art. I attended two of the ten films, both of which were written by Peter Handke. They were present at the screenings, and were interviewed afterwards. The first film, The Goalie’s Anxiety at the Penalty Kick, was an adaptation of Handke’s novel, which gained him an international reputation. Peter Handke was pretty hot in the early 70s. I had read his plays, but the novel made the deepest impression; I read it three times. I saw the film when it opened and remember finding it riveting and disturbing.

The story, in brief outline, tells you nothing of its effect on the viewer. A kind of nihilist fable, it follows Bloch, a professional soccer goalie, in a deadpan chronicle of human passivity: Bloch lets the winning goal score…Bloch checks into a cheap hotel…Bloch has pickup sex with a woman…Bloch reads the soccer scores in the paper…Bloch has sex with another young woman, then murders her…Bloch leaves town and hooks up with a former girlfriend…Bloch plays games with her little girl…Bloch reads about the murder and the soccer scores in the paper…Bloch plays the jukebox…Bloch watches a local game, commenting on the action. THE END.

The originality is not in the plot – a number of existentialist writers have told similar stories, including Dostoyevsky and Camus – but none had, I thought, so emphasized the stupefying banality of the situation. I thought so at the time, and its power has not diminished.

Handke seemed to pull back from the abyss, if only slightly, in the next film, The Wrong Move, which Wenders filmed in 1975. Wenders said at the screening that he didn’t change a single line of dialogue from Handke’s script. It’s a modern retelling of Goethe’s “Wilhelm Meister”, a classic bildungsroman. It concerns a young man living with his mother who decides to leave so that he can have the life experience necessary to become a writer. True to its source, it is stiff and meditative, with every character – save a near-mute Nastassja Kinski in her first role – speechifying the most highfalutin drivel to anyone within earshot.

Hardly cinematic, you’d think, but it’s surprisingly entertaining. Handke’s special skill is wryly amusing dialogue in odd juxtapositions. Wilhelm meets people the first time, and they all join him on his journey of self-discovery, as if their role in life was to wait for him to show up. Most improbably, this includes Hanna Schygulla (!), who notices him through a train window and follows him all over Germany, pleading for him to “satisfy her”. And yet, by the end of the journey, Wilhelm’s feeling that he has wasted the entire experience, and made all the “wrong moves”, is also wrong; the film attains a moral perspective by suggesting that the apparently random, passive observation of the real world is necessary for maturity and insight.

Wenders likes to have his actors speak to each other in long, long takes, as in The Wrong Move, when everyone tells of their dreams the night before as they walk along a mountain road. Even in a bad print (belying Wenders’ assurances before the screening), this scene is still spectacular. But Goalie has just been restored, and Robbie Mueller’s cinematography can be seen again in all its glory.

Interestingly, the actor playing the goalie-murderer is more appealing than the aspiring writer, who was rather smug and mopey. But nuanced acting has never been a major concern for Wenders. He casts each film as well as the budget allows, and his instincts are good. The acting in both films was at least OK, but the only actor making a strong impression was Ivan Desny in The Wrong Move, playing an industrialist who gives lodging to the travelers.

There’s a special pleasure in again seeing those films that you admired many years ago, especially when the filmmakers are there to introduce them.